|

| Mom, college counselor, teacher, zookeeper, police detecive |

Notice that last profession? Ah ha! I

haven't needed the other three professionals as experts yet, but if I ever have a mystery set in a college, a private school, or a zoo, I'll be set. The fourth daughter, Suzy, became a policewoman and, later, detective in Ames, Iowa. I guess this didn't surprise me since her father was a detective in Illinois during his professional career. But, strangely, Ms. Owens didn't attribute her interest in the criminal justice system to her father. What also surprised me was that Suzy was the youngest, tiniest, and most freckles-on-her-nose daughter. I have a hard time seeing her in a Kevlar vest, toting a gun. But she is.

Recently, I wrote a crime scene for my second mystery, and I passed it by Detective Owens so she could tell me how a detective would look at it versus how an author might write it. This resulted in two weeks and four re-writes. I would like to think she got no satisfaction whatsoever in asking her former English teacher to

"re-write until it's perfect," a phrase I seem to vaguely remember from my teaching conversations with her years ago.

I interviewed Detective Owens for my blog, and these were her answers:

Q: How did you happen to get into this line of work?

A: I didn't plan on being a police officer when I graduated from college. I thought I wanted to work with at-risk children. But I did an internship at the police department, loved it, and loved the people. They happened to be going through a hiring process and I was encouraged to apply. But I would really like to make this clear: I went into this work to make a positive difference in peoples' lives, not to drive fast cars and shoot guns.

Q: What are your credentials?

A: I have a BS in psychology with minors in criminal justice and Spanish from Iowa State University [1999.] I also graduated from the Iowa Law Enforcement Academy with peace officer certification [2000], and I have a Master's in criminal justice from Simpson College [2012.]

Q: What is your typical day like, or is there a typical day?

A: On patrol, I had a lot more variety in my day. But now, as a detective, I make and receive a lot of phone calls, do computer work and report writing, make

interviews. Sometimes my job entails search warrants, testifying in court, or processing a crime scene such as a recovered stolen vehicle or a burglary scene.

Q: What is the most frustrating part of your job?

A: I guess the most frustrating thing

might be the fact that many times there is not a doubt that the suspect has committed the crime, but I don't have the evidence to charge. This is especially true in cases of sexual violence, for both women and children, where the public opinion can lead to stereotyping and doubt toward the victim. If I do have probable cause to charge, it will be another frustrating road trying to get the victim's story told, with no real protections from the law. The defendants get all sorts of protections, while the victims have very few.Q: How do you do this work--homicide and sexually-based crime work--without getting emotionally upset?

A: I make sure I have healthy outlets for stress: exercise, talking to others, stepping away from it all as needed. Sometimes I get emotional, but realize I'm just a small part in the whole process, and I have to tell myself to do the best in my role.

Q: What kinds of crimes bother you the most?

A: Sex offenses, with domestic violence a close second. These cases have such a stigma, and it is so hard to move forward with judges and juries.

Obviously, I couldn't go into great detail with Suzy about the various cases she's worked, but from her answers I find it clear that she is neck-deep in the kind of work with which I have no experience

from my own career. This makes her a sensational expert for my mysteries. I can reseach, read cases, and check out books from my local coroner, but having first-hand experience nearby is a wonderful consequence of teaching for so many years. Thank you, Detective Suzy Owens, for being there when I have questions, and especially for not laughing when they are stupid questions.

.jpg) |

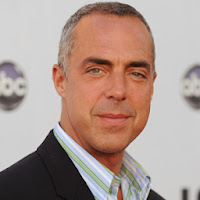

| They obviously take their work seriously. Detective Owens is second from the right. |